Espera, ¿Cómo Sabes Hablar Español? - a Chinese Diaspora Story

Daisy Loo, Victoria’s mom, as a baby

I never fail to notice when strangers at Mi Pueblo market or our favorite taqueria in San Jose start to wear a familiar look of shock the instant my mom races off speaking her fluent, effortless Spanish. My mom was born and raised in Leon, Nicaragua, which is about the last thing most people would guess if they didn't already know her. I often get asked how a Chinese family like my mom's found their way to Central America, let alone Somoza's Nicaragua of all places. My mom likes to tell me that my grandpa had a vision that communism was coming to China and he just knew he had to get his family out. As luck would have it, my grandpa's search through his familial network quickly bore fruit. His uncle, along with some friends from the same small Chinese village in Guangdong Province, had started a convenience store business in Nicaragua. He promised to help my grandpa set up a small convenience store (my mom describes it as a Target but without groceries and instead of being a chain it was just two stores) that would provide him with enough income to support his family out there. So, in 1946, my grandparents set off on a 40 day boat voyage from Guangdong to Leon. Shortly after they arrived, my eldest aunt was born, followed by three sons, and lastly, my mom, the youngest of five.

My mom doesn’t recount many stories about her childhood in Nicaragua, but on the rare occasions when she does, she often tells stories about working at their family store. All the siblings would take turns working shifts at the register after school and on the weekends. Her most vivid memory is of the warehouse in the back where they stored supplies and how much she hated having to retrieve something from there because she was convinced it housed a bat. Oh, and she also claims it was haunted. Away from the convenience store, she wasn’t surrounded by a lot of other Chinese kids. There were hardly enough Chinese immigrants to even form a community. A few of my grand uncle's business associates would visit or stop by on their way to the nearby town. To overcome this, my grandma and grandpa did their best to kindle a sense of Chinese culture among their family. While Spanish is their first language, my mom and her siblings can all speak Cantonese fluently thanks to their parents communicating with them solely in their native tongue. It often was a secret form of communication their family would use to talk to each other without others overhearing. These days, my mom and her siblings prefer their own native language, Spanish, with each other, and speak English or Cantonese with the rest of us. They preserve their Nicaraguan roots just as their parents had preserved their own native language and culture.

Being Chinese in Nicaragua in the 1950s had its challenges. Their store would often be the target of theft. My mom can still, from memory, recite the racist chants directed at them by other locals. Eventually, my grandma started to look towards the United States. Like most immigrants to America, the promise of better education, new wealth, and vast opportunity called to her. She had also heard of the large Chinese community in San Francisco and several relatives and friends from her same Chinese village had already immigrated there. My mom’s eldest sister met and married a Korean war veteran and was the first to leave for America. My mom went next on a visa sponsored by her sister’s new husband. She can recall the exact day on December 5,1972 at 12 years old and 11 months, boarding a Pan Am airplane, and landing in SFO. Scared and by herself, she began to settle into a new life living with her sister. Her parents didn’t immigrate until five years later in 1977, after sending over each of their children as soon as money allowed and visas became available.

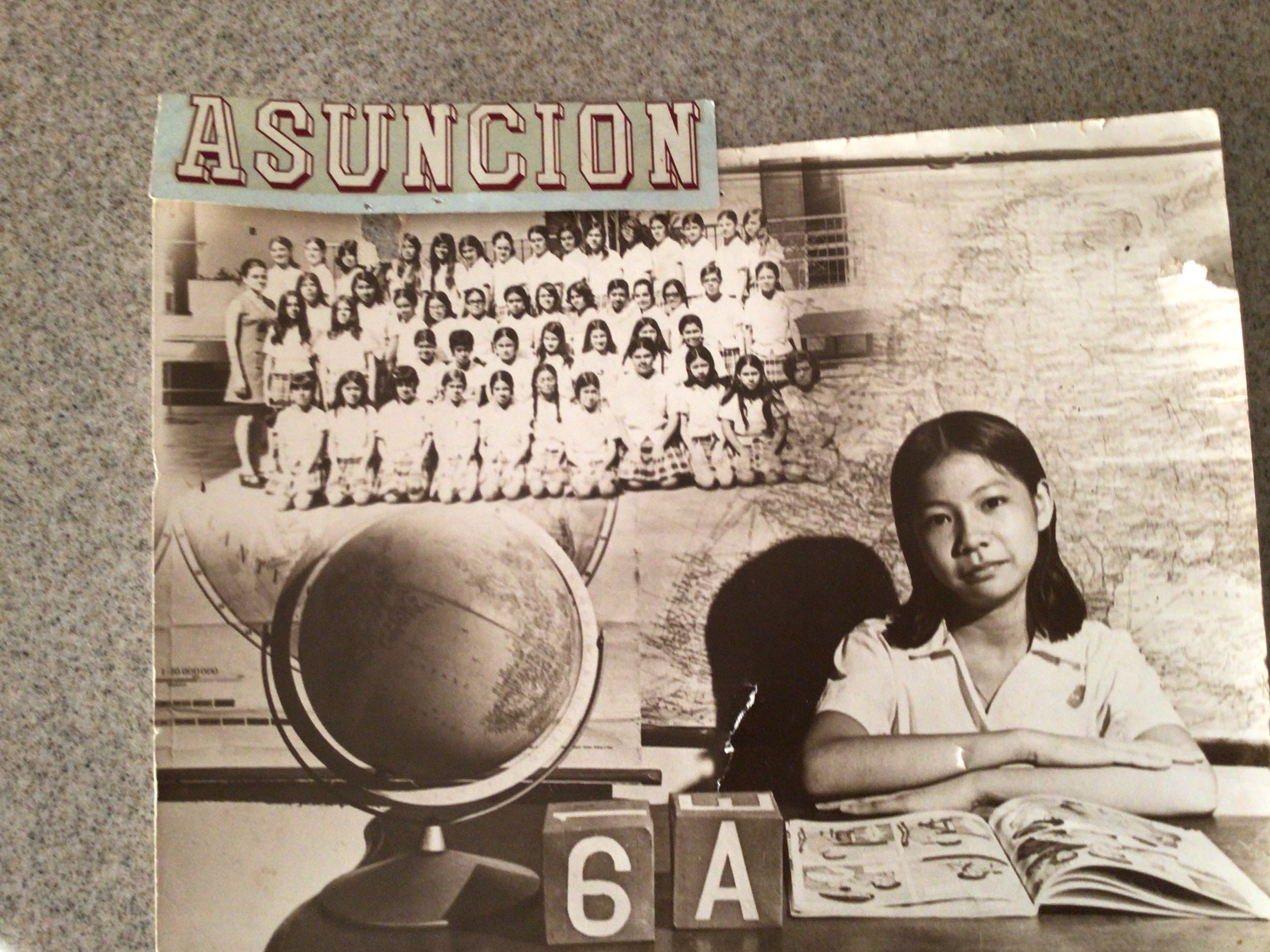

Daisy with her sixth grade class in Nicaragua

She quickly learned being Chinese in America in the 1960s also had its challenges. School was entirely in English and my mom had to learn a whole new language that did not come easily. It was difficult for her to make friends at a crucial age in her life, but she does fondly remember how kind one of her teachers was who made her feel welcome at a school she felt she didn’t belong. She said he was always patient with her and would assign her a buddy to help with her assignments. I asked her if she had done normal American high school things. Go to prom? Parties? Football games? Spirit rallies? Not a single one. Her high school experience could be summarized by her sitting alone under her locker studying to catch up.

Slowly and over time, my mom became more comfortable with America as her home. Luckily, there was the support of a Chinese community that my mom and her family could communicate with in Cantonese in San Francisco. She made friends by joining a Chinese youth association group which eventually led her to meeting my dad, a Hong Kong born Chinese who immigrated to America at the age of six. My parents raised three children as a manifestation of their hybrid culture. Outwardly, we all have the fiercely independent spirit typified by the sense of rebellion ingrained in the American culture. At home, our parents made sure to temper our individualism by instilling in us the values and virtues of filial piety, a hallmark of Chinese family culture. They bought a house in the suburbs, sent their kids to college, and lived what most would describe as the American Dream.

My mom has now been in America for 50 years. She has never returned back to her hometown in Nicaragua, afraid of what might not exist there anymore in a country plagued by war. She plans to go to China to see the Great Wall for the first time next year. She is a trilingual speaker of fluent Spanish, English, and Cantonese, though she will often talk to me in a mixture of all three (Spachinglish as I like to call it). I can see different parts of her identity come out depending on the situation. She negotiates business and calculates numbers in Spanish since that’s how her brain has been wired to do basic arithmetic. She peels and cuts fruit for her children in the same way all Chinese parents demonstrate their care and love. She loves eating pizza and driving around to all of the great national parks America has to offer. She identifies as Nicaraguan by birthright, American by preference, and Chinese by ethnicity.

Victoria Loo lives in San Francisco, only a short drive away to San Jose where her mom, Daisy Loo, now lives and works as a secretary at a middle school. Daisy loves her job being able to help students who are the age she was when she came to America.